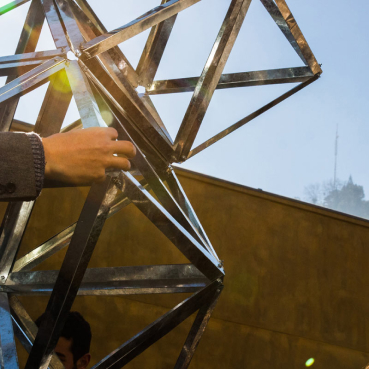

- Investigación y Creación La interdisciplina como campo de investigación supone un potencial de visibilidad e identidad del Campus Creativo, y es por esto que el equipo y sus colaboradores fortalecen el desempeño y la mecánica de trazar puentes inéditos entre las disciplinas que se imparten en el CC como una forma de mejoramiento continuo, velando siempre por el aseguramiento de la calidad académica.

surgió al alero de las facultades de Ingeniería, Economía y Negocios, y Campus Creativo– tiene como objetivo mejorar la calidad de vida y bienestar de las personas en las ciudades, a través de la generación de nuevo conocimiento multi e interdisciplinario, en torno al urbanismo y la planificación urbana.

Desarrollar investigación aplicada interdisciplinaria en temas de planificación urbana y territorial, generación de conocimiento individual y colectivo, tanto inter como multidisciplinar

Puedes revisar los proyectos mas relevantes donde objetivos académicos y profesionales se relacionan entre sí coherentemente, contemplando tus propósitos de tipo personal

Descubre nuevas ideas e inspírate en nuestras conferencias, donde expertos y profesionales de diversas áreas comparten su conocimiento y experiencias para impulsar tu crecimiento.

Investigación y Creación

La interdisciplina como campo de investigación supone un potencial de visibilidad e identidad del Campus Creativo, y es por esto que el equipo y sus colaboradores fortalecen el desempeño y la mecánica de trazar puentes inéditos entre las disciplinas que se imparten en el CC como una forma de mejoramiento continuo, velando siempre por el aseguramiento de la calidad académica.

- Investigación y Creación La interdisciplina como campo de investigación supone un potencial de visibilidad e identidad del Campus Creativo, y es por esto que el equipo y sus colaboradores fortalecen el desempeño y la mecánica de trazar puentes inéditos entre las disciplinas que se imparten en el CC como una forma de mejoramiento continuo, velando siempre por el aseguramiento de la calidad académica.

surgió al alero de las facultades de Ingeniería, Economía y Negocios, y Campus Creativo– tiene como objetivo mejorar la calidad de vida y bienestar de las personas en las ciudades, a través de la generación de nuevo conocimiento multi e interdisciplinario, en torno al urbanismo y la planificación urbana.

Desarrollar investigación aplicada interdisciplinaria en temas de planificación urbana y territorial, generación de conocimiento individual y colectivo, tanto inter como multidisciplinar

Puedes revisar los proyectos mas relevantes donde objetivos académicos y profesionales se relacionan entre sí coherentemente, contemplando tus propósitos de tipo personal

Descubre nuevas ideas e inspírate en nuestras conferencias, donde expertos y profesionales de diversas áreas comparten su conocimiento y experiencias para impulsar tu crecimiento.